Patrick Lencioni contends in his The Advantage: Why Organizational Health Trumps Everything Else in Business, that the interpersonal dynamics among employees of a company will more often predict success or failure of a company than will other factors. We often assume that competition, or supply chain, or customer demand are the primary determinants of success. Lencioni posits that organizational health is even more important.

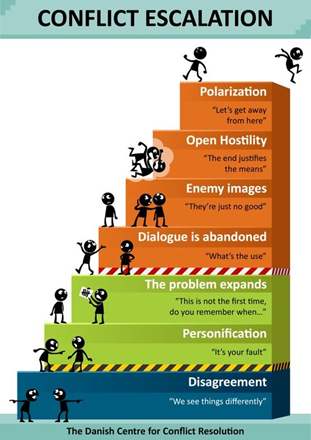

Who hasn’t worked in a company where there was conflict between employees? What is less quantified nor appreciated is the cost of conflict. Workplace Fairness West helpfully surfaced an infographic from The Danish Center for Conflict Resolution that illustrates the escalating forms of workplace conflict.

One sees how minor disagreements can grow. When dialogue between colleagues has ceased, the organization immediately starts losing momentum. If disagreements grow to hostility, or worse to disgust, then the organization no longer has its eyes on the ball. Members of the organization are spending so much time and attention managing their internal dynamics, that they lose sight of the market dynamics. The organization is destined to falter.

The question is not whether or not conflict exists. Of course it will exist. Organizations have people, and people will have different views that can manifest as conflict. Rather, if organizational health is THE defining indicator of success (as Lencioni insists), then the critical question is how do the members of an organization deal with and resolve their conflict?

Frédéric Laloux proposes a fascinating solution to this intractable problem in his book Reinventing Organizations. First he suggests that there are several different organizational models that organizations embody. In an earlier post entitled “Matching People and Structures,” I suggested that one key to workplace satisfaction is making sure that one’s personality type is properly matched to the organization’s structures and practices where one works. (If you don’t feel aligned with the practices of your organization, maybe there’s a better organizational paradigm waiting for your out there.)

Laloux categorizes different types of organizations by color to avoid associating a personal judgment through the label he used. In quick summary from the Reinventing Organizations Wiki the five main types of organizational paradigms are:

- RED: In the Red paradigm, there is a dominant exercise of power by the boss or leader to keep others in line. Fear is the glue of the organization. In general, conflict is handled by suppression, power or dominance, and strict rules are enforced by fear of consequences…

- AMBER: The Amber paradigm has formalized roles within a hierarchical pyramid structure and top-down command and control (what and how). Stability is valued above all and is maintained through clearly defined roles and processes…

- ORANGE: In the Orange paradigm, there is also a hierarchical structure, but management is by objective (definition of the what; with more freedom on the how). In many Orange organizations, although there are formal conflict resolution procedures, conflict is often not well addressed. Although individuals are often encouraged to resolve disagreements by themselves, conflict may often need to be settled by intervention from a third party. This is most often done by referring the issue to the boss or by deferring to HR policies and procedures. These procedures create a level of objective independence from “the those” in conflict…

- GREEN: The Green paradigm again uses a classical pyramid structure, but with a stronger focus on empowerment. Green organizations have values-based cultures that include principles of integrity, respect, and openness. There is a large investment in fostering collaboration, communication, problem solving and drafting agreements that meet underlying needs. These processes can sometimes remove the source of conflict. When they do arise, conflicts can take a long time to resolve as groups seek to find a harmonious solution. However, the boss is usually the final arbiter in conflict situations…

- TEAL: In Teal organizations, conflict is seen as a natural part of human interaction and, when safely supported, is often viewed as healthy and creative. Conflict handled with grace and tenderness can create possibility and learning for all involved. In Teal organizations time is regularly devoted to surface and address conflicts in individual and group settings. Often formal, multi-step conflict resolution practices are used and everyone is trained in conflict management. Conflict is restricted to the parties involved, and mediators, or peers who might be asked to serve on a mediating panel. Such a panel rarely has the responsibility to impose a solution. The focus is instead on helping the involved parties find a solution…

(https://reinventingorganizationswiki.com/en/theory/conflict-resolution/)

TEAL organizations are described as “self-managing organizations.” Many of the organizing principles of self-management may be out of reach for most companies today, but important aspects of TEAL conflict management might still be applicable to organizations of different paradigms.

In any organizational paradigm, it is helpful to document the process of how conflicts are resolved.

In self-managing organizations, having a clear and well understood conflict resolution process helps people raise issues. Typical conflict resolution mechanisms include: one-on-one discussion, mediation by a peer and mediation by a panel. Some organizations also use team or individual coaching to work through an upset.

For example, :

- In the first phase, the two people sit together and try to sort it out privately.

- If they can’t find a solution agreeable to both, they nominate a colleague they both trust to act as a mediator. The mediator doesn’t impose a decision. Rather he or she supports the participants in coming to their own solution.

- If mediation fails, a panel of topic-relevant colleagues is convened. Again the panel does not impose a solution.

- If resolution is not found, the founder or president might be called into the panel to add to the panel’s moral weight (but again, not to impose a solution).

(https://reinventingorganizationswiki.com/en/theory/conflict-resolution/)

The most important aspect of this process is that the individuals in conflict are forthright with each other. If they can’t find constructive resolution alone, they summon mediators to help them find common ground. As U.S. Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis said in 1913, “Sunlight is the best disinfectant.” Keeping dialogue open between the warring parties minimizes the negative practices that erode mutual respect and constructive collaboration. This is a cornerstone of organizational health, and will directly contribute to competitive advantage in the marketplace.